Written by Frank Hood- Associate Director of Policy and Partnerships at Hepatitis B Foundation!

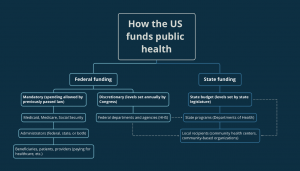

The COVID-19 pandemic put a spotlight on why countries need a robustly funded public health system that can respond to the needs of its citizens quickly. In the United States, that public health system is a patchwork of federal, state, and local departments, agencies, and programs. Each has their own rules and regulations, which can be challenging to navigate. You might have a hard time seeing how it all works together without falling apart. And you might struggle to understand how resources can find their way to the local health centers and community-based organizations doing much of the important health work on the ground. This blog post provides a basic overview of how public health funding works within the United States.

Hundreds of federal departments, agencies, and programs funnel money into the public health system of the United States. One of the more familiar organizations is the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Among its many health-related functions, HHS handles disease prevention and outbreak response through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and provides health coverage for underserved and older Americans through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Other departments like the Department of Agriculture (USDA) may not seem like a key source of health funding, and yet support dietary health initiatives and help states build rural medical facilities through infrastructure investment programs.

The amount of funding these departments, agencies, and programs receive varies yearly. Some funding, like for Medicare and Medicaid, doesn’t require an annual vote from Congress (known as “mandatory spending” in policy-speak) and is just paid for as expenses are incurred. Other funding, like for the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), requires a yearly vote of Congress as well as sign-off by the President. This is known as discretionary spending. Most US public health programs fall in the discretionary spending category. That vote happens each year after the House and the Senate go through a formal process to determine how much money every department, agency, and program in the entire federal government receives. This process also includes specifying any special instructions or conditions associated with the funding like restrictions on how the money can be spent or requesting a status report on the impact of a specific program

If Congress can’t agree on funding levels by the start of the new fiscal year, then a government shutdown occurs. In those instances, any non-essential federal program funded by discretionary spending would be forced to suspend operations, while state and local programs would still be able to function but would not receive federal funds during that time.

Once Congress approves funding levels, federal funds and agencies begin the process of distributing money to their various internal programs and to states and other localities. In the simplest terms, many agencies will send money to states in the form of grants that the states apply for by listing how they would use the money and what positive impact it will have on the state. The amount of funding that passes down to states depends on the function of the agency. State health departments receive the largest percentage of their funding from federal sources, so the grant-making process can lead to states competing for limited federal funds. Federal funds make up anywhere between half and two-thirds of states’ total health funding.

Much of the remaining funding for state health departments comes from their state legislatures. Each state has their own specific process, but most states mirror the federal approach of having their legislatures determine how much state funding should be given to various departments, agencies, and programs in the state and any restrictions on the use of that funding. Other sources of public health dollars include fines, fees, charitable donations, and public-private partnerships.

Generally, state health departments send their dollars to local health departments, which deliver direct care or education on the ground. The funding the state keeps is often used to pay for state-wide health systems like health surveillance, emergency response, and prevention education. How states determine where money goes varies, but there are usually similarities to how federal departments and agencies determine which states should receive what funding with grant applications.

Once local health departments and community-based organizations have funding in-hand, they then must spend it according to the rules and regulations set by the source (Congressional instructions, federal agency requirements, state requirements, etc.).

At this point, you see the complex tapestry of public health funding in action in your community: the health screenings at the local fair, the vaccine drives at your local place of worship, and even when your child brings home a pamphlet from a health educational program held at school. It’s all public health funding in action.

In addition to public funds, some programs are funded in part directly through donations from people like you. If a public health program means a lot to you, see if you can help the organization who put it together by volunteering, spreading the word or donating.

References:

https://www.cdc.gov/about/organization/mission.htm

https://www.cms.gov/

https://www.usda.gov/our-agency/about-usda/mission-areas

https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47106

https://www.crfb.org/papers/qa-everything-you-should-know-about-government-shutdowns

https://www.astho.org/topic/public-health-infrastructure/profile/#activities

https://www.norc.org/PDFs/PH%20Financing%20Report%20-%20Final.pdf

https://www.norc.org/PDFs/PH%20Financing%20Report%20-%20Final.pdf

https://www.publichealthlawcenter.org/resources/state-local-public-health-overview-regulatory-authority