Please welcome guest blogger Charlotte Lee, a pre-med Duke University Senior who has a passion for global health. Charlotte recently learned first hand how viral hepatitis disproportionately impacts her community and how it tragically touched her own family.

Please welcome guest blogger Charlotte Lee, a pre-med Duke University Senior who has a passion for global health. Charlotte recently learned first hand how viral hepatitis disproportionately impacts her community and how it tragically touched her own family.

I walked into the first day of my internship ready to take on what I thought were the major public health crises of the world – malaria, AIDS, avian flu. Instead, my supervisor gave me a hefty stack of literature on hepatitis B. Sure, as a premed student I knew that hepatitis had something to do with the liver, but I was shocked to find out that hepatitis B was the most common serious liver infection in the world—one that chronically affects over 350 million people worldwide, including 1 in 12 Asian Americans—and I had never heard of it.

As a 21-year old Asian American who is passionate about global health, I felt cheated to only now discover that there is an infectious disease disproportionately affecting my community. Somebody should have told me about this! To then find out that it was completely vaccine-preventable – somebody should have told everyone about this!

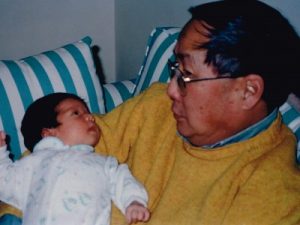

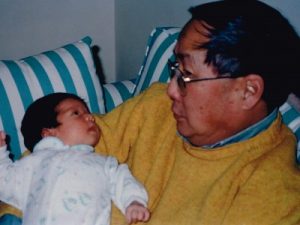

About halfway through my internship, I found out that my grandfather died from viral hepatitis that he contracted through a blood transfusion. Suddenly the disease had a face, and it was a smiling man with wide rimmed glasses who used to sit me on his lap and feed me popcorn. It now feels like my duty to spread the word.

Hepatitis B is transmitted through blood or body fluids and causes deadly liver disease, including liver cancer, in 1 out of every 4 chronically infected people. Meanwhile, the famous West Nile Virus causes serious illness in less than 1% of infected people.

So, what makes this disease so easy to ignore? Hepatitis B is unfortunately an invisible disease; it can take up to 20-30 years before symptoms appear, at which time cirrhosis or liver cancer may have already developed. Hepatitis B is a silent killer and it affects a population invisible to the media and policy. Anyone can get hepatitis B; however, people born in countries outside the US that have not instituted a strong hepatitis B testing and vaccine program have a large population (2 out of 3 people) who are unaware they are infected. Most get the disease at birth from their mothers who are chronically infected with hepatitis B. Many are impoverished and disenfranchised. Asian Americans make up more than half of hepatitis B cases in the US, but those from many other countries around the world are also at risk for having the disease.

However, the “it won’t happen to me, so I don’t care” rule doesn’t work for all diseases. Most people in the US don’t consider themselves at risk for AIDS, malaria, or tuberculosis, yet those diseases have plenty of name recognition.

One thing that AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis all have in common is their deadliness. AIDS killed 1.47 million people in 2010. But did you know that viral hepatitis (hepatitis B & C combined) killed 1.44 million that same year?

Its symptomless nature also makes it hard to visualize. While other diseases invoke graphic images of illness, hepatitis devastates the liver. Most people probably don’t really know where their liver is located.

What frustrates me most is that it is a preventable disease, one that we can eradicate. The hepatitis B vaccine is one of the safest and most effective immunizations available, and it protects you for life. The CDC recommends all babies receive the vaccination at birth, yet many major hospitals in NYC are not immunizing newborns, with some vaccination rates as low as 20%.

Hepatitis B needs public health champions to get it into the spotlight. Policies need to be passed to fund much-needed education, surveillance, and treatment programs. Doctors should be educated about it, tests should be automatically ordered, and the government should pay for everyone to be vaccinated. This system doesn’t yet exist, but thankfully there are people working tirelessly towards it.

Monday was World Hepatitis Day 2014. This year, the Viral Hepatitis Testing Act was introduced in the House and Senate to provide $80 million over three years for prevention, testing, and linkage to care. This is the second term this bill has been introduced, and now it’s time to pass it. Locally, the New York City Council just introduced a $750K viral hepatitis initiative for 2015. And just last week, Councilwoman Margaret Chin was on NBC talking about the first ever NYC Hepatitis B Awareness Week. My internship will soon end, but advocacy never rests. There is always more to be done.

Charlotte Lee is a premed Duke University senior, where she studies Public Policy with minors in Global Health and Chemistry. This summer, she has been working on hepatitis B policy issues at the Charles B. Wang Community Health Center in New York City, where she was co-coordinator of the first-ever NYC Hepatitis B Awareness Week. She is passionate about health disparities and aspires to be an OB/GYN and women’s health advocate. Her biggest claim to fame is that she may have discovered a new species of sand fly last summer in the Peruvian Amazon (confirmation still pending).

Charlotte Lee is a premed Duke University senior, where she studies Public Policy with minors in Global Health and Chemistry. This summer, she has been working on hepatitis B policy issues at the Charles B. Wang Community Health Center in New York City, where she was co-coordinator of the first-ever NYC Hepatitis B Awareness Week. She is passionate about health disparities and aspires to be an OB/GYN and women’s health advocate. Her biggest claim to fame is that she may have discovered a new species of sand fly last summer in the Peruvian Amazon (confirmation still pending).

By Vivian Huang, MD MPH,

By Vivian Huang, MD MPH,