Are you or someone you know at risk for hepatitis B? You might be more at risk than you think, and since hepatitis B is vaccine preventable, it makes sense to get tested and vaccinated for HBV. Hepatitis B is the number one cause of liver cancer worldwide. The survival statistics for liver cancer are particularly grim, with a relative 16,6% 5-year survival rate. The hepatitis B vaccine also protects against hepatitis delta, the most severe form of viral hepatitis.

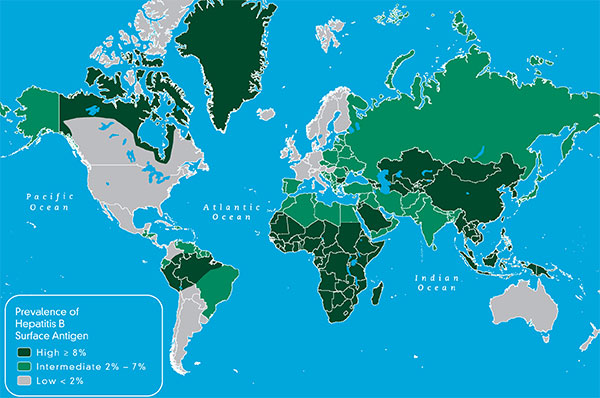

It is important to note that everyone is susceptible to hepatitis B. It does not discriminate. It infects, babies, children, teens, adults and seniors. It has no racial or religious bias, though it is certainly more prevalent among certain ethnic groups –mainly because it is endemic to the homelands of these communities. For example, if you look at the prevalence map for hepatitis B, you will see that in most of the world, hepatitis B is at an intermediate, (2-7%) or high HBsAg prevalence (>8%) level. Looking at the numbers, 2 billion people in the world, that’s 1 out of 3 people, have been infected with HBV and 257 million are chronically infected. That represents three-quarters of our world. Even if you aren’t living in these parts of the world, you may be traveling to some of these areas for work or pleasure, or perhaps your parents and other family members were born in HBV endemic areas. Since there are often no symptoms for HBV, and screening and vaccination may be lacking in some populations, HBV is transmitted from one generation to the next, with many completely unaware of their HBV status – until it’s too late.

People at risk for hepatitis B include the following: (not noted in a particular order)

- Health care providers and emergency responders due to the nature of their work and potential for exposure.

- Sexually active heterosexuals (more than 1 partner in the past six months)

- Men who have sex with men (MSM)

- Individuals diagnosed with a sexually transmitted disease (STD)

- Illicit drug users (injecting, inhaling, snorting, pill popping)

- Sex contacts or close household members of an infected person (remember, you may not know who is or is not infected)

- Children adopted from countries where hepatitis B is common (Asia, Africa, South America, Pacific Islands, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East) and their adopted families

- Individuals emigrating from countries where hepatitis B is common (see above)

- Individuals born to parents who have emigrated from countries where hepatitis B is common (see above)

- ALL pregnant women – because infants are so vulnerable to HBV (90% of infected infants will remain chronically infected, and HBV is very effectively transmitted from infected mother to baby.)

- Recipients of a blood transfusion before 1992

- Recipients of unscreened blood and blood products – sadly an issue in many parts of the world.

- Recipients of medical or dental services where strict infection control practices are not followed – sadly another issue in parts of the world.

- Kidney dialysis patients and those in early renal failure

- Inmates of a correctional facility

- Staff and clients of institutions for the developmentally disabled

- Individuals with tattoos and body piercings performed in a parlor that does not strictly adhere to infection control practices – it may be up to you to ensure proper infection control practices are followed.

- People living with diabetes are at risk if diabetes-care equipment such as syringes or insulin pens are inadvertently shared.

The good news is that hepatitis B is a vaccine preventable disease. There is a safe and effective, 3-shot HBV vaccine series that can protect you and your loved ones from possible infection with HBV. The earlier you are vaccinated, the better. In the US, a birth dose of the vaccine is recommended for all infants, since these little ones are most vulnerable to hepatitis. (90% of infected infants will live with HBV for life). HBV vaccination doesn’t give you a free-pass from other infectious diseases such as HCV or HIV, both without vaccines, so strict infection control practices should still be followed. However, HBV is a tenacious virus that survives outside the body for a week and is 50-100 times more infectious than HIV 3-5 times more infectious than HCV. Plus the HBV vaccine is actually an anti-cancer vaccine, so why not get vaccinated?

Hepatitis B isn’t casually transmitted, but in the right scenario, it is effectively transmitted. You may think that situation may never come about for you, or for your loved ones –especially your little ones who are so vulnerable to HBV. Some people travel to exotic lands with unsafe blood supplies and poor infection control practices, and sometimes they get sick, or require emergency dental or medical services, so they may be put at risk. Most people have had a lapse in judgment – sometimes it’s a one-time thing, sometimes it lasts for years, but the net-net is that it’s unusual to find someone who has not engaged in some sort of high-risk activity, whether intentionally or unintentionally. If you are properly vaccinated to protect against hepatitis B, you can cross that concern off your list.

B sure. Get screened. if you do not have HBV, get vaccinated and be hepatitis B free. If you discover you have HBV, talk to your doctor and have him refer you to a liver specialist who can better evaluate your hepatitis B status and your liver health.