(If you missed it, see part I) The second trip entailed the training of rural doctors. During the training course, we used a number of simple visuals to better get some basic ideas across. We wanted to drive home how common HBV was in China, and the number of Chinese people infected. We asked 10 people to stand up. They smiled with pride, having been selected, until they realized they were being identified as one of those possibly infected with HBV. The numbers dwindled as we went through the process of asking some to sit down representing those that had been infected, but resolved the virus, until finally, the last one standing represented someone with chronic HBV. This person was clearly horrified. This visual certainly drove the point home, but perhaps we were the ones educated by this process.

(If you missed it, see part I) The second trip entailed the training of rural doctors. During the training course, we used a number of simple visuals to better get some basic ideas across. We wanted to drive home how common HBV was in China, and the number of Chinese people infected. We asked 10 people to stand up. They smiled with pride, having been selected, until they realized they were being identified as one of those possibly infected with HBV. The numbers dwindled as we went through the process of asking some to sit down representing those that had been infected, but resolved the virus, until finally, the last one standing represented someone with chronic HBV. This person was clearly horrified. This visual certainly drove the point home, but perhaps we were the ones educated by this process.

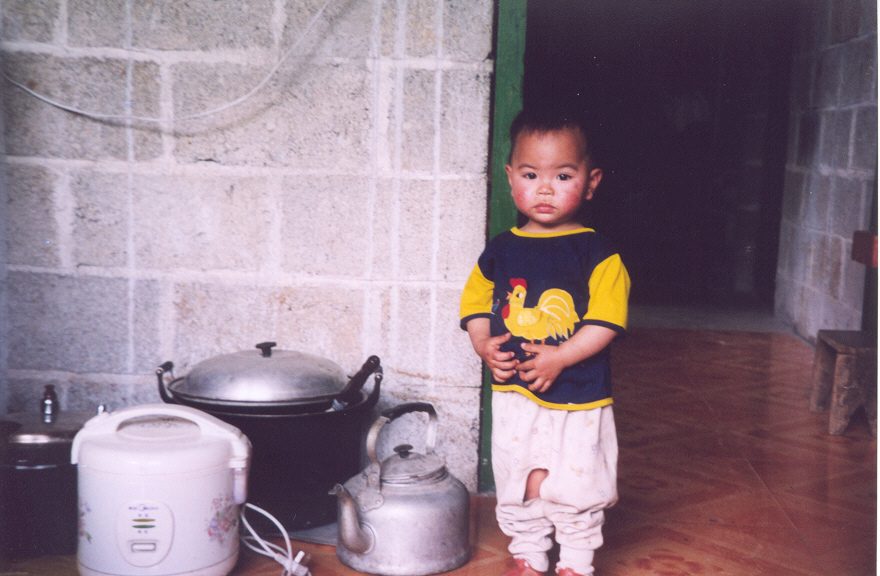

The Chinese people love children. I had a photo album of my children, which many enjoyed during the break. There was one photo with a picture of both my two children and my colleague’s two children. My colleague and I were traveling with two of the children and had not identified if either were infected. (As a result, we sat at every meal where most assuredly there was a large serving spoon in every dish…) There was only one child that could be “safely” identified. When I pointed the child out to them, I could hear them, speaking in English, saying “Yes, I knew it. Look at her. She’s sick… doesn’t look well.” I can’t even imagine what was said in Chinese. HBV is nearly always asymptomatic in children. All four children in the photo appeared equally healthy. At that moment, I was grateful these children were spared the taunts.

During the course of the visit, we made an impromptu stop at a hospital on the outskirts of one of the cities. We were shocked when we were permitted to enter the compound without pre-approval. It was not a sanitized visit like all of the other stops we made. We were traveling with a U.S. doctor, and I think the Chinese doctor we met was interested in speaking with her. The facility was well below the standards we had encountered elsewhere. The largest building on the compound was the “women’s facility”. We were not allowed in the building, nor were any pictures permitted of that particular building.

In another city we met with a conventionally trained doctor who had grown up in a very rural province, and was sometimes requested due to her rural background and familiarity. She told us of a recent rural visit, where hundreds of women had been infected with an STD. As a result of migration of workers into the cities, these women villagers are more often victims of diseases previously not seen in these areas. Sadly, many of the women were being infected due to the lack of precautions taken during the annual examination of women. The major culprit was the reuse of speculums that were not disinfected.

Finally, we met so many interesting, young Chinese, and heard so many wonderful stories like the one about a young university graduate who started the first online community of hbvers (that’s what they like to call themselves.) It would turn out to be the biggest in the world, and would provide much needed support for many isolated Chinese, living with HBV. There were also other stories, too, of how Chinese hbvers fought against discrimination by using a stand-in – either a paid “professional”, or other, loyal friends for their compulsory medical blood tests. Imagine living with the fear of losing everything just because of the results of a simple blood test.

I went to China, naively thinking I would make a difference. I was overwhelmed with the dire situation of those living with HBV. The experiences and stories were sobering and haunted me for months after returning. It was so personal. I certainly cannot fix this global problem on my own, but I will do everything possible, so that others may understand, just a little, the impact of living with hepatitis B in China.