Dr. Ilan Weisberg is a highly acclaimed gastroenterologist and hepatologist currently serving as the Chief of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at New York-Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital. He shares the Hepatitis B Foundation’s enthusiasm for advocacy and education surrounding hepatitis B and D, and was eager to provide the perspective of a healthcare provider on the current state of hepatitis delta screening and management, as well as some common misconceptions.

Dr. Ilan Weisberg is a highly acclaimed gastroenterologist and hepatologist currently serving as the Chief of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at New York-Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital. He shares the Hepatitis B Foundation’s enthusiasm for advocacy and education surrounding hepatitis B and D, and was eager to provide the perspective of a healthcare provider on the current state of hepatitis delta screening and management, as well as some common misconceptions.

A Shift in Provider Awareness and Knowledge

One of the first topics Dr. Weisberg spoke about was how unaware he was about hepatitis delta until recently. He discussed the ongoing issues with a general lack of knowledge about hepatitis delta in the United States, and how this is the most common reason for many of the current challenges seen today. When asked what led to his and other providers’ shift in knowledge, he credited the improvements with hepatitis C awareness and treatment with some of the shift, as well as the potential for new treatments for hepatitis B and D. “Every time there is a promise of a treatment or a cure or intervention, then I think it helps engender more enthusiasm for screening.”

Hepatitis Delta Prevalence and Screening Practices

Dr. Weisberg sees hundreds of patients who are living with hepatitis B virus (HBV). New York, and especially Brooklyn, have so many cultural communities coming from countries where hepatitis B is common. Hepatitis D is a much smaller percentage of his patient population. Dr. Weisberg was a co-author on a study that looked back through electronic medical records (EMRs) for all hepatitis B surface antigen positive (HbSAg+) patients at his former health system to identify how common hepatitis delta virus (HDV) testing and prevalence were. Across the entire health system only about 12% of HbSAg+ patients were tested for delta and among those individuals there was a 4% positive rate for HDV (Nathani et al., 2023).

One particularly concerning part of that study for Dr. Weisberg was the overall low rates of hepatitis delta screening. He notes that it is difficult to keep health care providers motivated to screen when the number of those with hepatitis delta is so low, and that creative solutions like automatic EMR suggestions may increase the likelihood of testing. About three years ago at his former clinic, Dr. Weisberg standardized a protocol for screening every existing and new patient living with hepatitis B for hepatitis delta at least once. This protocol is still being used in his current health system. “Even though the event rate is low, the clinical importance of finding these patients [is] very high” and he hopes that this approach will be widely adopted to more closely align with European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) recommendations compared to the current risk-based approach of the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD)(EASL, 2023; Terrault et al., 2018). Discussions on changing these American recommendations have been in circulation and plans to update them should be realized in the near future.

Dr. Weisberg believes that one of the reasons for the low testing is that hepatitis delta is considered a “rare disease” in the United States. He notes that the major differences in the number of cases among different countries means that one study in a specific geographic area cannot be generalized to the entire global prevalence. He hypothesizes that if there was true and accurate prevalence data across the globe, the number of cases would be higher than those estimated in the U.S. and globally today. One of the challenges in providing accurate prevalence data is knowledge about appropriate testing, which Dr. Weisberg recalls encountering in his clinical career. When he arrived at his former health system, they were only testing for hepatitis delta antigen rather than the hepatitis delta antibody (anti-HDV), which is the appropriate initial test to perform. True prevalence rates are important for improving our understanding of who is affected by hepatitis delta, and with new therapeutics on the horizon, it is vital to identify patients who are hepatitis delta-positive so that they can participate in trials and be ready to receive treatments once approved.

Thoughts on Universal Reflex Testing

Dr. Weisberg mentioned that his current health system does not have the HDV test set up as a reflex test (automatic testing for HDV when one tests positive for HBV, using the same blood sample) straight from HbSAg+ to anti-HDV and from anti-HDV to confirmatory HDV RNA, but they are working on getting that established. “In a place like Brooklyn where we have enormous populations from hot spots of endemicity for delta, like Moldova and Mongolia, it might be very cost-effective, but in other parts of the country it may not be, and it is hard to have a universal strategy that is not universally cost-effective.” He also highlighted the need to be able to reliably check across databases to avoid repeated testing upon new emergency room visits, providers, etc.

Risk Factors for Hepatitis Delta

According to the AASLD, identified risk factors for hepatitis delta include persons born in regions with reported high HDV endemicity, persons who have ever injected drugs, men who have sex with men, individuals living with hepatitis C (HCV) or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), persons with multiple sexual partners or history of sexually transmitted disease, and those with persistently elevated levels of the liver enzymes ALT and AST, despite low levels of HBV DNA. Based on Dr. Weisberg’s experience he has not found these risk factors to be entirely representative of his hepatitis delta patient population. The same study he conducted on hepatitis delta screening found that, by following the AASLD risk-based screening guidelines alone, about 18% of positive cases would have been missed. Of those positive cases, the patients tended to be younger and had significantly notable increase in liver disease progression and incidence of liver cancer. Dr. Weisberg encourages the testing of all hepatitis B-positive individuals to ensure the capture of all cases and linkage to appropriate care.

One major misconception among providers that Dr. Weisberg noted is that hepatitis delta is commonly referenced as a virus only seen in people living with HIV and people who use injection drugs (PWID). This translates to higher screening rates in those groups and leaves out a focus on those immigrant communities from highly endemic countries that can be very heavily affected by the virus.

Case Management Recommendations

Management of hepatitis delta patients requires a uniquely tailored approach for each case, but Dr. Weisberg outlined some of the general recommendations that he makes for his HDV+ patients. Since hepatitis D is so damaging to the liver, a main concern is keeping their liver as healthy as possible. This means reducing alcohol consumption to avoid developing alcohol-related liver disease and completing liver cancer surveillance (ongoing screening using non-invasive methods to detect early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)). Dr. Weisberg recommends seeing your hepatologist once or twice a year and he personally checks patient labs and viral loads every six months, and transient elastography (FibroScans) every three years or so to check the stiffness and fat changes in the liver. Other screening tools such as ultrasounds, alpha fetoprotein (AFP) markers, and Fibrosis-4 values are appropriate ways to stay updated on the liver health of all hepatitis delta-positive individuals. Most importantly, Dr. Weisberg stresses the need for a strong relationship between the hepatologist and the primary care provider in the long-term management of viral hepatitis patients, and a team-based approach with other providers in the clinical setting.

In terms of treatment options for hepatitis delta, the only currently available therapeutic is pegylated interferon alpha, which in Dr. Weisberg’s experience has not been effective in reducing his patients’ viral loads and tends to cause a lot of additional difficulties for his patients in their daily lives. He recommends careful consideration of which patients should be put on interferon treatment. In cases of contraindications such as diagnosis of autoimmune disease or severe risk of progressive disease, there is a possibility to appeal for compassionate use therapy for some treatments not yet fully approved in the United States. One such therapy is Hepcludex, the recently available treatment, which is presently only approved for prescription in Europe.

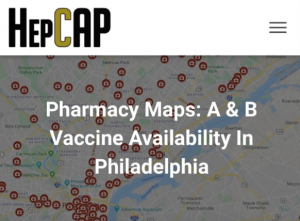

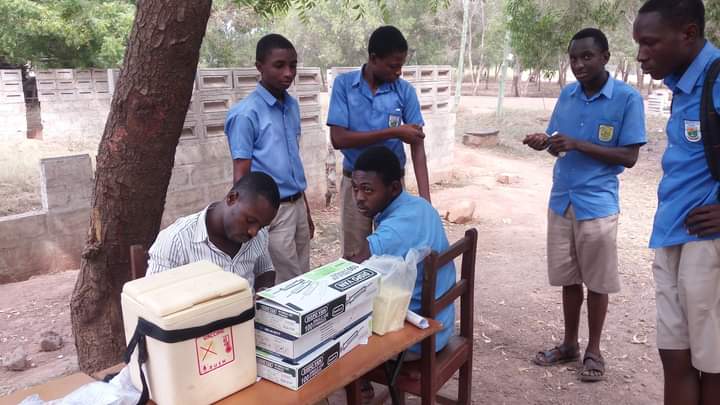

Finally, Dr. Weisberg’s management approach always involves the family of affected individuals, and discussions of how to keep transmission low for any who may be vulnerable to hepatitis B and D. One commonly cited reason for low delta screening rates for providers is “Why screen for people without a treatment?” Since hepatitis delta is highly transmissible, knowing one’s status allows the patient to be mindful about preventing exposure and infection of other household members, sexual partners, etc. Dr. Weisberg is a strong advocate for promoting hepatitis B vaccination in immigrant and adult populations (the vaccine also prevents hepatitis delta) and testing for the presence of hepatitis surface antibody (HbSAb) among close contacts of individuals living with hepatitis B and delta, to ensure low transmission rates.

The Promise of Future Treatments

“Every patient with [hepatitis] delta should be treated for [hepatitis] delta” but the major missing component is available treatments. Dr. Weisberg believes this to be the largest unmet need for his patients, but he emphasized hope for approval of treatments in the future. The availability of compassionate use therapy is a strong indicator for future approval since this was not always an option. Additionally, bulivertide (Hepcludex) is approved in the European Economic Area but is not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States. Dr. Weisberg explained that most information suggests that the delay in approval is more likely related to the need for reliable manufacturing and supply chain efficiency rather than a concern about the safety of the drug itself. (The FDA has not requested any further clinical trials, which is promising.) One common misconception in the provider community is that there will never be a cure for hepatitis B, but Dr. Weisberg remains confident in the progress being made towards both treatments for hepatitis D and a cure for hepatitis B.

Dr. Weisberg is one of many compassionate and knowledgeable physicians that manage people living with hepatitis B and D. If you need a provider, use our Physician Directory to find one near you!

References

European Association for the Study of the Liver (2023). EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on hepatitis delta virus. Journal of hepatology, 79(2), 433–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.05.001

Nathani, R., Leibowitz, R., Giri, D., Villarroel, C., Salman, S., Sehmbhi, M., Yoon, B. H., Dinani, A., & Weisberg, I. (2023). The Delta Delta: Gaps in screening and patient assessment for hepatitis D virus infection. Journal of viral hepatitis, 30(3), 195–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvh.13779

Terrault, N. A., Lok, A. S., McMahon, B. J., Chang, K., Hwang, J. P., Jonas, M. M., Brown, R. S., Bzowej, N., & Wong, J. B. (2018). Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology, 67(4), 1560–1599. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29800

World Health Organization: WHO. (2023, July 20). Hepatitis D. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-d

Amina asked her doctor how she could get rid of this virus. Her doctor explained to her that there is no cure for hepatitis B, but antiviral treatment options do exist. While she may not be able to completely get rid of the virus, she can help protect herself from serious conditions such as hep B related cirrhosis or liver cancer with treatment. Amina’s doctor encouraged her to get treatment to prevent any serious problems from occurring. He also mentioned that treatment for hepatitis B is safe and effective. This did not make any sense to Amina. She thought to herself that if a treatment wouldn’t cure her of the disease, then there is no point in taking it. She felt healthy and did not show any symptoms. After the doctor suggested treatment options, she said that she will wait for the cure.

Amina asked her doctor how she could get rid of this virus. Her doctor explained to her that there is no cure for hepatitis B, but antiviral treatment options do exist. While she may not be able to completely get rid of the virus, she can help protect herself from serious conditions such as hep B related cirrhosis or liver cancer with treatment. Amina’s doctor encouraged her to get treatment to prevent any serious problems from occurring. He also mentioned that treatment for hepatitis B is safe and effective. This did not make any sense to Amina. She thought to herself that if a treatment wouldn’t cure her of the disease, then there is no point in taking it. She felt healthy and did not show any symptoms. After the doctor suggested treatment options, she said that she will wait for the cure. After moving to the U.S., Amina had gotten busy with school and work and did not follow up with her primary care doctor for years. Amina experienced stomach pains from time to time but they often went away on their own. On one occasion, her stomach pain worsened. She had to take a few days off from work to get better using home remedies, but they didn’t help. Finally, she went to the doctor’s office to learn more. She discovered that she had liver cancer. Her doctor referred her to a hepatologist (a liver specialist) for further treatment.

After moving to the U.S., Amina had gotten busy with school and work and did not follow up with her primary care doctor for years. Amina experienced stomach pains from time to time but they often went away on their own. On one occasion, her stomach pain worsened. She had to take a few days off from work to get better using home remedies, but they didn’t help. Finally, she went to the doctor’s office to learn more. She discovered that she had liver cancer. Her doctor referred her to a hepatologist (a liver specialist) for further treatment.  The hepatologist explained to Amina that hepatitis B can lead to liver cancer without monitoring and treatment. Even though a cure is not available, treatment options do exist, and they help in slowing and preventing serious liver disease, liver damage or liver cancer. If Amina had started antiviral treatment on time, she could have saved her liver. The doctor recommended chemotherapy for Amina to treat the cancer. Not only did her medical bills go up but Amina felt physically and mentally exhausted by the procedures. She advocates for everyone living with hepatitis B to get treatment if they need it and not wait for the cure. She also participates in advocacy efforts to make treatment options more affordable for people living with hepatitis B.

The hepatologist explained to Amina that hepatitis B can lead to liver cancer without monitoring and treatment. Even though a cure is not available, treatment options do exist, and they help in slowing and preventing serious liver disease, liver damage or liver cancer. If Amina had started antiviral treatment on time, she could have saved her liver. The doctor recommended chemotherapy for Amina to treat the cancer. Not only did her medical bills go up but Amina felt physically and mentally exhausted by the procedures. She advocates for everyone living with hepatitis B to get treatment if they need it and not wait for the cure. She also participates in advocacy efforts to make treatment options more affordable for people living with hepatitis B.