The Coalition Against Hepatitis for People of African Origin (CHIPO) is a community coalition that was co-founded and is led by the Hepatitis B Foundation. CHIPO is made up of organizations and individuals who are interested in addressing the high rates of hepatitis B infection among African communities in the U.S. and globally. Over the past year, CHIPO has grown its membership to include over 50 community-based organizations and federal agencies, all of which are working to meet the common goals of raising awareness about hepatitis B among African communities, and increasing rates of screening, vaccination, and linkage to care. This month, we spoke with Samuel Addai of the Falcons Health Foundation (FHF) based in Accra, Ghana. Samuel and his team continuously work to reduce the disease burden of viral hepatitis B and C throughout the country. Concerning hepatitis B specifically, Ghana is considered to be a highly endemic country, with an estimated hepatitis B prevalence of 12.3% to 14.4% (Efua et al., 2023). Samuel spoke with us about the barriers he and his team face battling viral hepatitis in Ghana, the strategies they use to overcome those challenges, his reason for doing this vital work and his hopes for the future.

Could you please introduce yourself and your organization?

My name is Samuel Addai. I’m from Ghana. I was born and raised here. I am the founder and the leader of Falcons Health Foundation. I have about 15 [employees] of which five are public health officers. And then also three of them are lab technicians. And I have three national officers. I have two midwives as well, and two community health workers.

Could you tell me a little bit about what some of FHF’s programs are that specifically address hepatitis and other health concerns in Ghana’s communities?

We create public awareness about viral hepatitis B and C. We are also advocates for those with hepatitis. And then we also give treatment guidelines; and do treatment services for people, as well as free health screenings. If we didn’t do this, people would not be bold enough to come out. There is stigmatization of these diseases. We explain that hypertension and high blood sugar causes a lot of health conditions. We explain to them signs and symptoms of HIV and viral hepatitis. Once we are done with this explanation, if they allow us, then we start the screening.

What is the main geographic area in which FHF works?

Ghana has 16 regions. We started in the capital Accra. The capital is very big and we cannot go to every area. What we normally do is select some areas from which more complaints are coming. Especially Circle and then Madina and Ashaima [areas of Ghana]. We also go to part of the Ashanti region and to Bono region. We also go to the Northern part of Ghana, Tamale, and the Central part, Winneba. These are very big regions, so we only go to certain parts. The rest, we have yet to decide.

What are some of the biggest challenges in addressing hepatitis and other health concerns? How have you worked to overcome these? Are there any additional resources that would be helpful to have?

There is a lack of knowledge regarding viral hepatitis in the regions we service. We realized that the kind of health information that they recieive…[is] misinformation. And then also some people, due to cultural practices and their beliefs, do not seek treatment or testing. We did brief interviews and found that they believe that viral hepatitis and HIV are a result of juju, or spiritual forces, witches, and wizards. Some people also think that viral hepatitis and HIV diseases are a curse from their ancestors. Some of these issues, since they are due to a lack of knowledge and education, what we normally do is educate them and explain to them that witches and wizards are not the cause of these diseases. We try as much as we can to educate them. We explain to them the cause of these diseases. We do intensive education. Some people pretend not to believe us, but then they will come back later and say ‘check for me.’ Later they also laugh and talk about what they used to believe. Their response tells us that they are ready to take a test.

Lack of sustained financing is our burden. We find it difficult in terms of the transport system. And also social media platforms, most of them give mistrust. They say that the viral hepatitis vaccine, the side effects are harmful to health. We normally try as much as we can to overcome the misinformation.

And then also, some equipment and materials for testing can be a problem. And if we are able to get a center, we could do testing permanently. Currently, we do not have a center that we can use as a permanent place for testing. When we go to the areas, maybe we can just sit in a place at the roadside or in classrooms, which is not very helpful. We also do tents at the park. We give our information to [people]. We use information centers in the area to announce that we are back at a particular place and that people should come to us. So if we are able to get a small facility at least, which could take maybe 100 patients, it would be very helpful for us. We are doing very difficult work here and no one is paying us. This is a sacrifice that we are taking on.

What do you think are some of the biggest barriers in raising awareness and addressing rates of hepatitis screening and linkage to care?

The biggest barriers that we can encounter is the language barrier. In Ghana, the entire country is not speaking one language. English language is our official language. Those who do not attend schools, those who do not have any educational background find it difficult to understand English language. A day before our program, we invite some people in that particular area and we negotiate with them and ask if it is possible for them to translate their language to their people. And then also we do sign language, especially for disabled people. Another major barrier is stigmatization. Everybody feels shy and thinks “maybe this person knows me well” or “maybe this person knows my family.” Many people fear coming out in public to get tested.

What are your favorite parts about your job? What got you interested in this work?

What I love most and my favorite part here is the impact that we are making in communities. The testimonies that people are sharing to us. We really love this. At least people have received a good health impact in their lives.

Saving lives is my priority. Saving lives is what got me interested. I studied general medicine and then later also I studied public health.

Any other thoughts or ideas you’d like to share for improving health in Ghana, at both the community and national levels?

I believe that supporting these programs are very, very important so that we can reach out to many people because it seems that many people do not have this particular information yet. I believe that many people are not getting awareness. Information is very important, so if many people received this information, it would be helpful for the program.

We have a plan to develop an electronic data management system and surveillance system. Ghana does not currently have a hepatitis B or C elimination plan in place. We want to develop this so that it can help us keep data.

We want to reduce mother-to-child transmission by ensuring testing for pregnant women is free to all pregnant women. Before someone can get tested, they pay out of their pocket. Many people do not have the money to get the test, so we want to do that for them so that their health can be improved by knowing their status.

Let me add this too: Treatment is only available in teaching hospitals and this must be fully financed by the patient. Currently there is no public budget line for testing and treatment. We want to do free health screening so that this will help improve people’s health.

Do you have any final thoughts that you’d like to share?

What I can say is that me and my team, we have been able to acquire land and we want to be able to use it as a center. If we are able to get the necessary support, we can put up a small facility so that many people will know our exact location. In case there is any issue, they can visit our center. The problem here in Ghana, the government is not supportive at all. Even the government health facilities, they are having problems. They lack a lot. We don’t get support from the government. The people who received services from us support us. Later, they come to us and say “I’m okay, [my health is] fine now” and out of their joy, they support us. Other than that, we do not have support.

Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me and for sharing more about the great work FHF has done and will continue into the future!

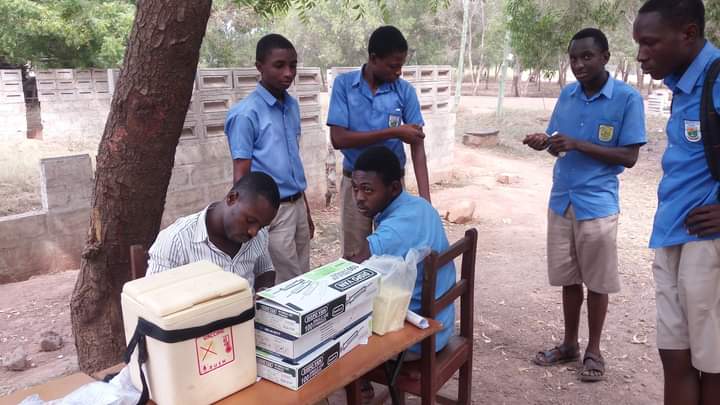

Below are some photos that Samuel shared of his team doing their incredible work across Ghana.

Efua, S.-D. V., Adwoa, W. D., & Armah, D. (2023, January 20). Seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus infection and associated factors among health care workers in southern Ghana. IJID Regions. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2772707623000097#:~:text=In%20Ghana%2C%20the%20prevalence%20of,the%20general%20population%20%5B7%5D.