The holidays are over and it’s time for a fresh new year- a fresh new start! Have you made your New Year’s resolutions yet? Do you need some suggestions or help creating your list? Here are some ideas!

- Be healthier.

- One of the most popular New Year’s resolutions in the US is to be healthier, whether it is to eat healthier, get more exercise, and/or to head over to the gym more often. There are studies that continue to show the importance of exercise, which favorably impacts the health of your liver as well. Although there is no specific diet for chronic hepatitis B, studies show that eating cruciferous vegetables such as cabbage, broccoli, and cauliflower is good for the liver. Green, leafy vegetables are also good for the liver. All of these veggies tend to naturally protect the liver against chemicals from the environment. The American Cancer Society’s diet, which includes low fat, low cholesterol, and high fiber foods is a good, general diet to follow. It is also good to avoid processed foods and foods from “fast food restaurants”. These foods along with too many foods high in saturated fats, and foods or sugary drinks with refined sugars and flours may result in fatty liver disease, which can also harm the liver. When possible, eat whole grains and brown rice. For more suggestions, check out the World Health Organization’s healthy diet and CDC’s tips for staying healthy.

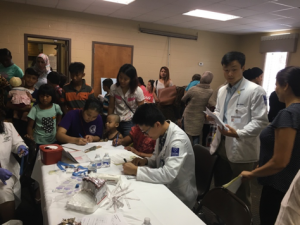

- See your doctor more often.

- We encourage those chronically infected to be regularly monitored by a liver specialist, treated when necessary, and to make lifestyle changes that help keep the liver healthy. The most important thing is to find a doctor who is knowledgeable about hepatitis B, who can help manage your infection and check the health of your liver on a regular basis. The doctor will take blood tests, along with a physical examination of the abdominal area and perhaps an ultrasound, to determine the health of the liver. Talk to the doctor and see what he or she recommends. Don’t forget to get copies of test results for personal files to see how test results change over time

- Stop drinking/limit alcohol.

- Chronic hepatitis B and alcohol is a dangerous mixture. Studies have shown that even small amounts of alcohol can cause damage to an already weakened liver. Avoiding alcohol is one decision someone can make that will greatly reduce the risk of further liver disease. It is also important to avoid smoking and other environmental toxins. For example, avoid inhaling fumes from paint, paint thinners, glue and household cleaning products, which may contain chemicals that could damage the liver. Keep in mind that everything that you eat, drink, breathe in or absorb through the skin is eventually filtered by your liver and toxins are removed. If you can limit the toxins in your body, your liver will benefit.

- Pursue your dreams.

- Don’t let your hepatitis B status stop you!! Find friends, family members, colleagues, and/or doctors who can support and encourage you to learn about your hep B status. Become an advocate for yourself, just like our #justB storytellers!

Start off your resolutions with attainable goals! You don’t have to quit cold turkey and completely eliminate certain foods. Take it step by step! Keeping a journal and tracking your progress will help you keep an eye on those resolutions this year. Even if you break your New Year’s resolutions, don’t be discouraged! Everyone goes through pitfalls and experiences lows. The important thing is to start over again when you break your resolutions!

Check out our previous post on New Year’s resolutions for more ideas for your resolution this year!

The

The