Highlighting the Relationship between hepatitis B and Liver Cancer

October marks Liver Cancer Awareness Month, an initiative highlighting this significant, but under-prioritized public health concern. Unfortunately, people living with hepatitis B have greater risk of developing liver cancer, and this risk is even higher for people born in countries where hepatitis B is more prevalent (Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2014; Chayanupatkul et al., 2017). Because of this, the Hepatitis B Foundation (HBF) conducted a study among foreign-born communities in the U.S. who are heavily impacted by the hepatitis B virus (HBV) to assess awareness levels about the connection between HBV and liver cancer. HBF used the perspectives and ideas expressed during these focus groups to create culturally and linguistically tailored, community-focused awareness and educational materials, so that everyone has continuous access to user-friendly HBV and liver cancer information.

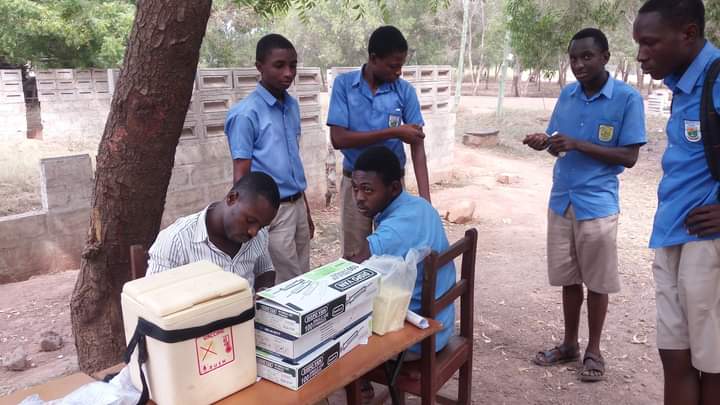

From April to September 2021, the HBF conducted focus groups with people from the Micronesian, Chinese, Hmong, Nigerian, Ghanaian, Vietnamese, Korean, Somali, Ethiopian, Filipino, Haitian, and Francophone West African communities. A total of 15 virtual focus groups took place, with 101 individuals providing their thoughts about what hepatitis B and liver cancer are, and insights into appropriate strategies to educate their greater communities on the connection between these two conditions. The resulting communications campaign aims to improve the public’s knowledge about the link between HBV and liver cancer, reduce hepatitis B- and liver cancer-related myths and misconceptions, and promote hepatitis B and liver cancer screening and early detection among Asian and Pacific Islander (API) and African and Caribbean immigrant communities. The ideas and experiences voiced by focus group participants also contributed to the development of informational liver cancer materials for community health educators to integrate into existing education programs for immigrant communities.

Summary of focus group findings:

All focus groups emphasized the need for educational materials to highlight the relationship between hepatitis B and liver cancer. Interestingly, people were more aware of liver cancer and its serious health consequences than they were of hepatitis B and how it is a leading cause of liver cancer. Many people had personal experience with liver cancer, having known family members, friends or other community members who have died from the disease. With this, participants believed that people will be more likely to practice healthy behaviors, like vaccination and routine screening, when they know that HBV can lead to liver cancer and know what behaviors can reduce their risk of liver cancer and death. When people learn about the benefits of vaccination (like full protection against HBV and reducing the risk of transmitting the virus to loved ones), and screening (keeping your liver healthy), and are provided with resources and tools to manage their health, they are empowered and are more likely to make healthy choices to reduce their risk of severe health outcomes.

When educating people about the connection between the two diseases, it is also important to address the widespread misconceptions about both hepatitis B and liver cancer, which contribute to shame and stigma surrounding each condition. Many focus group participants revealed that their communities believe that HBV is related exclusively to sexual promiscuity, injection drug use and poor hygiene, all of which lead to stigma against people living with hepatitis B (PLHB), who are believed to be “immoral” or “dirty.” These stigmatizing beliefs cause PLHB to become reluctant to seek care and treatment for the virus, and can discourage screening in the greater community because people do not want to be shamed by or isolated from their social circles. Additionally, participants discussed how their communities believe that liver cancer is only associated with alcohol and are unaware of the causal relationship between HBV and liver cancer. According to focus group participants, educational materials should include some information about how hepatitis B is transmitted and how it can lead to liver cancer if left untreated and unmanaged. One way to do this is by including the personal testimonials of PLHB and liver cancer in educational materials, who show the audience how they stay healthy and maintain a good quality of life while living with these diseases. As people see how one’s quality of life does not diminish, and learn from the stories of people living with hepatitis B or liver cancer, they may become more understanding of the diseases and supportive of their own community members who are living with them.

Focus group participants were also asked to identify communication strategies that would be acceptable for their community groups. As for in-person communication, educational sessions should take place in settings where people feel safe, including community-based organizations, religious spaces, and healthcare offices. These sessions, as emphasized by participants, should be facilitated by trusted messengers, like patient navigators, doctors, and faith leaders, or other people who have a shared culture with the audience. Demonstrating cultural respect during face-to-face communication is also of utmost importance. Certain communities emphasized that it is especially important to have gender-specific messengers when discussing topics like sexual transmission of hepatitis B (Taylor et al., 2013; Cudjoe et al., 2021).

Educational campaigns should also be strategic when discussing community-specific risk, as it is important to discuss each community’s risk without placing blame on a specific group. Despite the fact that countries in the Asian-Pacific and sub-Saharan African regions have endemic levels of HBV and the highest global incidence rates of liver cancer (Zamor et al., 2017), many focus groups explained that their communities consider HBV and liver cancer to be Western diseases, since the conditions are often not discussed in home countries, and are therefore unaware of both the severity of the diseases and their personal risk. Focus group participants agreed that informational material can group highly impacted communities together when presenting prevalence rates and risk factors, so as to reduce shame associated with HBV and liver cancer of one group while increasing audience awareness of their risk (Parvanta & Bass, 2018).

Experiences of Community Focus Group Facilitators

Community participation and leadership was of utmost importance in this project. Two focus group facilitators recounted their experiences of recruiting and conducting focus groups with their communities. The first was the leader of the Cantonese focus group.

Despite being nervous about how it would turn out, one facilitator spent time thinking about the project. They chose to conduct the focus group in Chinese (Cantonese), the “native language of the participants,” and hoped that communicating in Cantonese would increase participant engagement, especially when discussing their “lived experience of the disease.”

“Prior to convening the Zoom meeting, I had provided a one-on-one orientation to each participant about the theme of the focus group and expectations. As a result, everyone was ready and able to fully participate, and speak openly at the meeting. It was a fruitful discussion among the five participants. Everyone brought up their perspectives and insights about stigma and health education strategies to the community. They had expressed a sense of fear and emotional distress when they were made aware of the relationship between hepatitis B and liver cancer. They raised lots of questions on hepatitis B transmission, testing and vaccination, and liver cancer and treatment, and were very interested to learn more about necessary lifestyle changes if they contracted chronic hepatitis B.

At the end participants had requested a follow-up session to learn more about HBV and liver cancer. They will be excited to know about the release of the newly developed Chinese-language educational materials on both diseases, which came together because of their contributions. I would suggest Hepatitis B Foundation and UC Davis to host an in-person workshop to present the new education materials. That would be a meaningful outreach and education to the local Chinese and Asian communities.”

Another facilitator shared their thoughts and insights regarding the focus group they conducted with their African immigrant community. They felt that being a facilitator for this study was an “enlightening experience,” especially as they uncovered their community’s healthcare awareness as it relates to hepatitis B and liver cancer. They continued to share:

“Running the focus group gave me valuable insights into the knowledge gaps and misconceptions surrounding HBV within the African immigrant population. Through open and honest discussions, we uncovered specific areas where education and awareness initiatives can have a significant impact. Many participants needed to understand the transmission, prevention, and available resources related to these diseases. Understanding these nuances is crucial in tailoring our educational materials effectively.

Regarding the study findings, it was evident that there is a pressing need for culturally sensitive educational resources. The unique challenges African immigrants face, including language barriers and cultural differences, highlight the importance of creating materials that resonate with our community members. Moreover, the findings emphasized the urgency of dispelling myths and stigmas associated with HBV and fostering a supportive environment for affected individuals and their families.

As for the materials produced for the campaign, I am genuinely impressed with the effort and attention to detail put into their creation. The content is informative and culturally relevant, making it relatable to our community. Using images, culturally familiar scenarios, and visuals ensures that these materials will significantly raise awareness about HBV in my community.

When disseminated effectively, these materials will empower African immigrants with the knowledge they need to protect themselves and their loved ones. By addressing the specific concerns and questions raised during our focus group sessions, these resources have the potential to bridge the information gap and promote proactive healthcare practices within our community.”

Conclusion

The overall goals of these materials are to facilitate improved hepatitis B and liver cancer awareness, increase testing and prevention behaviors, and reduce misconceptions about the two diseases to ultimately reduce HBV- and liver cancer-related death. Thanks to the insights and recommendations from the focus group participants, educational hepatitis B and liver cancer materials were created in a culturally sensitive and linguistically appropriate manner for a number of communities in the U.S. who are greatly impacted by the two diseases. To reach a broad audience, the materials will be available on multiple communication platforms and in multiple languages. This first part of the community-informed educational campaign can be found on the HBF’s Liver Cancer Connect website now. All materials will be fully uploaded and available to the public for further community education starting in February of 2024. Translated materials and messages tailored for audio and video formats will also be uploaded on a rolling basis.

References

Chayanupatkul, M., Omino, R., Mittal, S., Kramer, J. R., Richardson, P., Thrift, A. P., El-Serag, H. B., & Kanwal, F. (2017). Hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Journal of Hepatology, 66(2), 355-362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2016.09.013

Cudjoe, J., Gallo, J.J., Sharps, P., Budhathoki, C., Roter, D., & Han, H-R. (2021). The role of sources and types of health information in shaping health literacy in cervical cancer screening among African immigrant women: A mixed-methods study. Health Literacy Research and Practice, 5(2), e96-e108. doi: 10.3928/24748307-20210322-01

Department of Health and Human Services. (2014). Action plan for the prevention, care, & treatment of viral hepatitis. Department of Health and Human Services.

Hong, Y.A., Juon, H.S., & Chou, W.Y.S. (2021). Social media apps used by immigrants in the United States: Challenges and opportunities for public health research and practice. mHealth, 7, 52. doi: 10.21037/mhealth-20-133

Hong, Y.A., Yee, S., Bagchi, P., Juon, H.S., Kim, S.C., & Le, D. (2022). Social media-based intervention to promote HBV screening and liver cancer prevention among Korean Americans: Results of a pilot study. Digital Health, 8, 20552076221076257. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076221076257

Joo, J.Y. (2014). Effectiveness of culturally tailored diabetes interventions for Asian immigrants to the United States: A systematic review. The Diabetes Educator, 40(5), 605-615. DOI: 10.1177/0145721714534994

Parvanta, C., & Bass, S. (2018). Health communication: Strategies and skills for a new era: strategies and skills for a new era. Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC.

Porteny, T., Alegria, M., del Cueto, P., Fuentes, L., Lapatin Markle, S., NeMoyer, A., & Perez, G.K. (2020). Barriers and strategies for implementing community-based interventions with minority elders: Positive minds-strong bodies. Implementation Science Communications, 1, 41. doi: 10.1186/s43058-020-00034-4

Taylor, V.M., Bastani, R., Burke, N., Talbot, J., Sos, C., Liu, Q., Jackson, J.C., & Yasui, Y. (2013). Evaluation of a hepatitis B lay health worker intervention for Cambodian Americans. Journal of Community Health, 38(3), 546-553. doi: 10.1007/s10900-012-9649-6

Zamor, P. J., deLemos, A. S., & Russo, M. W. (2017). Viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma: Etiology and management. Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology, 8(2), 229–242. https://doi.org/10.21037/jgo.2017.03.14

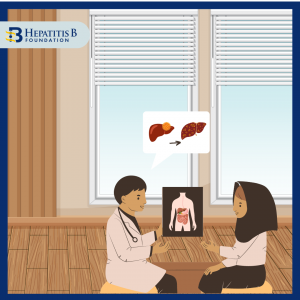

Amina asked her doctor how she could get rid of this virus. Her doctor explained to her that there is no cure for hepatitis B, but antiviral treatment options do exist. While she may not be able to completely get rid of the virus, she can help protect herself from serious conditions such as hep B related cirrhosis or liver cancer with treatment. Amina’s doctor encouraged her to get treatment to prevent any serious problems from occurring. He also mentioned that treatment for hepatitis B is safe and effective. This did not make any sense to Amina. She thought to herself that if a treatment wouldn’t cure her of the disease, then there is no point in taking it. She felt healthy and did not show any symptoms. After the doctor suggested treatment options, she said that she will wait for the cure.

Amina asked her doctor how she could get rid of this virus. Her doctor explained to her that there is no cure for hepatitis B, but antiviral treatment options do exist. While she may not be able to completely get rid of the virus, she can help protect herself from serious conditions such as hep B related cirrhosis or liver cancer with treatment. Amina’s doctor encouraged her to get treatment to prevent any serious problems from occurring. He also mentioned that treatment for hepatitis B is safe and effective. This did not make any sense to Amina. She thought to herself that if a treatment wouldn’t cure her of the disease, then there is no point in taking it. She felt healthy and did not show any symptoms. After the doctor suggested treatment options, she said that she will wait for the cure. After moving to the U.S., Amina had gotten busy with school and work and did not follow up with her primary care doctor for years. Amina experienced stomach pains from time to time but they often went away on their own. On one occasion, her stomach pain worsened. She had to take a few days off from work to get better using home remedies, but they didn’t help. Finally, she went to the doctor’s office to learn more. She discovered that she had liver cancer. Her doctor referred her to a hepatologist (a liver specialist) for further treatment.

After moving to the U.S., Amina had gotten busy with school and work and did not follow up with her primary care doctor for years. Amina experienced stomach pains from time to time but they often went away on their own. On one occasion, her stomach pain worsened. She had to take a few days off from work to get better using home remedies, but they didn’t help. Finally, she went to the doctor’s office to learn more. She discovered that she had liver cancer. Her doctor referred her to a hepatologist (a liver specialist) for further treatment.  The hepatologist explained to Amina that hepatitis B can lead to liver cancer without monitoring and treatment. Even though a cure is not available, treatment options do exist, and they help in slowing and preventing serious liver disease, liver damage or liver cancer. If Amina had started antiviral treatment on time, she could have saved her liver. The doctor recommended chemotherapy for Amina to treat the cancer. Not only did her medical bills go up but Amina felt physically and mentally exhausted by the procedures. She advocates for everyone living with hepatitis B to get treatment if they need it and not wait for the cure. She also participates in advocacy efforts to make treatment options more affordable for people living with hepatitis B.

The hepatologist explained to Amina that hepatitis B can lead to liver cancer without monitoring and treatment. Even though a cure is not available, treatment options do exist, and they help in slowing and preventing serious liver disease, liver damage or liver cancer. If Amina had started antiviral treatment on time, she could have saved her liver. The doctor recommended chemotherapy for Amina to treat the cancer. Not only did her medical bills go up but Amina felt physically and mentally exhausted by the procedures. She advocates for everyone living with hepatitis B to get treatment if they need it and not wait for the cure. She also participates in advocacy efforts to make treatment options more affordable for people living with hepatitis B.