Please introduce yourself and describe what you do and where you work.

My name is Dr. Carla Coffin, and I am a hepatologist at the University of Calgary in Alberta, Canada, I am a clinician scientist who does research on hepatitis B and this year I am the president of the Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver. Calgary is the founding/coordinating site for the Canadian Hepatitis B Research Network, which helps lead a collaboration of researchers, scientists, and practitioners across Canada for hepatitis B research and advocacy.

How common is hepatitis delta in your location or nationally?

That is an excellent question because until relatively recently, we didn’t know that much about how common hepatitis delta was in Canada. Most studies were single-site, single-center studies, showing about 1% prevalence overall in people living with hepatitis B. Then the Canadian Hepatitis B Research Network in collaboration with the National Microbiology Lab and the National Reference Lab in Canada did a study, led by Dr. Carla Osiowy, that showed, based on a retrospective screening of cases that were referred for hepatitis delta testing, that the prevalence was about 3% overall. Now, there’s more recent data that is consistent with that approximation of about 3%. We are also conducting a study that shows that for people who are being referred for delta screening, their overall positivity is about 4%. These are specific studies, but if you are just looking at universal screening rates of everyone who is living with hepatitis B who is potentially at risk for hepatitis delta, and not necessarily pre-identified, it’s much lower, maybe only about 1% or 2%.

What are the current screening recommendations and protocols in Canada for hepatitis delta virus (HDV)?

Historically, the recommendations from our major guidelines have been risk-based screening. So, people that are coming from areas where we know hepatitis delta is endemic. People that may have other risk factors such as a history of injection drug use or clinical characteristics that might trigger the clinician to suspect hepatitis delta co-infection. But based on that, I think that people are missed or are not diagnosed, so there’s inaccurate epidemiology just on risk-based screening. Our updated hepatitis B guidelines, which hopefully will be published in 2025, are more consistent with other expert recommendations to do universal screening. So at least a single, one-time test will be recommended for all people living with hepatitis B, to screen for hepatitis delta. And many of our laboratory partners agree with these recommendations. So hopefully there will be a change in the near future for that.

Do you think the reported prevalence is accurate or are people missing?

I would say that the current reported epidemiology of about 2 to 3% is likely to be accurate, but without having a robust universal screening program and robust reporting of hepatitis delta-positive cases, then I can’t say that with 100% confidence. One of the metrics that the Public Health Agency of Canada is advocating for is to have more robust data collection on hepatitis D epidemiology. That’s one of the calls by Action Hepatitis Canada, which is an advocacy group.

So, I think the epidemiology is accurate based on the data we have, but I can’t be 100% confident until we do more robust studies.

What do you think could help to address some of the underdiagnosis of hepatitis delta globally?

We need universal screening to ensure that people are diagnosed and not just rely on risk-based testing. We talk about knowing where hepatitis delta is endemic, but we should also recognize that there are probably countries where the prevalence is higher, but because of a lack of screening, we don’t know where it is actually endemic.

Even in my practice and just this week, we came across a patient that had been followed in our clinic for 15 years with hepatitis B and we only diagnosed this person with hepatitis delta recently, because we hadn’t screened it before.

And I think the other important thing is to increase awareness among health practitioners. A specialist might know about hepatitis delta, but a primary care provider or non-hepatologist would be left less aware. Increase education of healthcare practitioners to say, you know, if your patient has hepatitis B, they should be screened for hepatitis delta.

What do you usually do to help patients manage hepatitis delta?

Well, I think the first thing is you need to explain as clearly as possible exactly what hepatitis delta is and how you get hepatitis delta. How do you prevent it from spreading?

Explain how it’s transmitted by sharing blood and body fluids, highlighting that if you get the vaccine for hepatitis B, that protects you against both B and delta. Then explain what delta can do to your liver and how it can increase your risk of getting liver damage, or liver scarring or cirrhosis, how it increases your risk of getting liver cancer, and the importance of having regular checkups on your liver. So, regular blood tests and regular ultrasounds for monitoring for liver disease and for liver cancer. A lot about management is empowering the patient and giving them educational resources. Then the other thing is to discuss the treatments. There is only one treatment approved for hepatitis B in Canada, and you can use it for hepatitis delta, and that’s interferon. That’s the only thing we can currently use to treat hepatitis delta.

If/when a new drug is approved in Canada, do you think distribution and uptake will be straightforward or do you perceive challenges?

Yes, there will be many challenges. Part of it stems from underappreciation of hepatitis B as well as hepatitis delta. So, if a new drug is approved, it may be a challenge just to raise awareness about it.

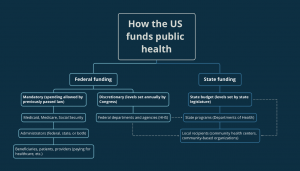

And the second thing is that health care is federally funded, but the funding is then sent to each jurisdiction. The provinces and territories decide how healthcare funding is spent, and then there’s a complex approval process. It starts with Health Canada approval and then there’s this pan-Canadian drug agency called CADTH, the Canadian Agency for Drugs & Technologies in Health, that reviews the medication and sees whether or not they would recommend it. Then each provincial agency looks at the review by CADTH and decides if they want to have it on the formulary.

So, it could be time-consuming, complex, and challenging because of these factors.

Can you describe some of the advocacy efforts in which you have been engaged on hepatitis delta at different levels, and with different stakeholders?

Yeah, so I’m happy to say we’ve been having some success with advocacy. So different stakeholders and partners include Action Hepatitis Canada, the Canadian Liver Foundation, and our professional organization, the Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver. Activities we have done include going to Parliament Hill in Ottawa and holding our Annual Viral Hepatitis Elimination Day on May 9th. We’ve done that now for three years. With the help of all these partners and stakeholders, we have been engaging various governments (so government ministers at the provincial level and at the federal level), and also working with our federal health agencies (so the Public Health Agency of Canada) and having discussions with them to increase the messaging about hepatitis delta.

Are there any messages about hepatitis delta that you would like to share with policy or decision-makers?

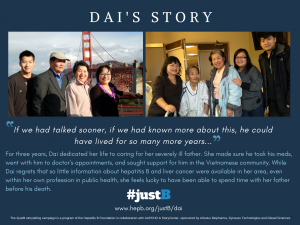

I think you need to start with the patient’s voice. What I found most striking when we were meeting with the different policy decision-makers and government officials was that the physicians or the experts could talk about hepatitis B and talk about hepatitis delta and you didn’t see the same impact, but we brought patients with us when we had our meetings and when the patients spoke up and talked about their lived experience, you could really see their story having a strong impact. Then, also try to support the work of our partners.

What are some possible programs or initiatives that can help raise the profile of hepatitis delta and improve participation in the care cascade?

A lot of the people affected by delta are non-Canadian born, so there are a lot of challenges in navigating the healthcare system and language barriers. If we had more in terms of language or translations, I think that would be a good way to increase participation in healthcare and potentially raise the profile. The second is the education of healthcare practitioners, going beyond the specialist, and talking to primary care and family doctors.

Also, perhaps starting at the community level, at a non-academic center to raise more awareness about hepatitis delta and involving people with lived experience. But that’s a bit more difficult because there are so many, at least in Canada, challenges with understanding the language and understanding that patients often have many other challenges that it’s hard for them to think about their health care.

Do you have any final thoughts on hepatitis or hepatitis delta?

There’s been a lot of progress on hepatitis B with the drugs that we have currently, the effective nucleoside analogs, and with the hepatitis B vaccine, of course. It’s a remarkable vaccine, but we need more research and investment in both basic science research to try and find a cure for hepatitis B, and more public health research and investment to reach those that are living with hepatitis B, to provide them treatment and limit financial barriers. Also, more research and investment for hepatitis delta and testing. There’s not even a standardized test for delta. So, my final thought would be that we’ve done a lot, we’ve made progress, but there’s still more work to be done, and we need more government and industry funding.