The Coalition Against Hepatitis for People of African Origin (CHIPO) is a national community coalition that is co-founded and led by the Hepatitis B Foundation and is comprised of organizations and individuals who are interested in addressing the high rates of hepatitis B infection among African communities in the U.S. Over the past year, CHIPO has grown its membership to include over 50 community-based organizations and federal agencies, all of which are working to meet the common goals of raising awareness about hepatitis B among African immigrant communities, and increasing rates of screening, vaccination, and linkage to care. This month, we are excited to highlight the work of one of our partners, the Hepatitis Aid Organization, and their Executive Director, Lutamaguzi Emmanuel. Please enjoy a recent interview with Lutamaguzi, as he describes his work, including successes and challenges building hepatitis care capacity and multi-national partnerships.

Could you please introduce yourself and your organization?

My name is Lutamaguzi Emmanuel, I’m a person living with hepatitis B, testing positive in 2016. I’m the executive director and team leader at the Hepatitis Aid Organization civil society organization that is supporting hepatitis elimination in Africa using multidisciplinary partnerships.

Could you tell me a little bit more about some of your organization’s programs and campaigns that specifically address hepatitis and other health concerns in your community

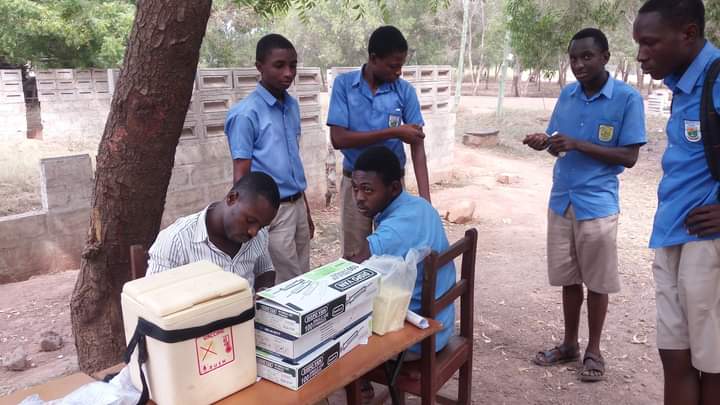

Our organization focuses mainly on four issues: advocacy, education, patient support, and research. For Uganda specifically, which is the first country we started working in, we have been able to push for the birth dose. We have been able to do a couple of awareness campaigns, and mobilize communities for uptake of services, testing, and vaccination. We have been able to support the Ministry of Health on capacity building for health workers, specifically those working in maternal health clinics. We have been able to engage cultural leaders for social mobilization. We have been also able to engage religious leaders. I mean it’s quite a lot.

We have many partnerships in academia, in Africa, in Uganda, in India, and we are trying to see how we can bridge the gap to inform our proposals and decision making. We have initiated the parliamentary health forum on hepatitis in Uganda, which supports hepatitis advocacy and seeing that things are really working on at the parliamentary level. We are also supporting the Ministry of Health in Uganda at the National Technical Working Group, where we have representation. We have a network of patients that we are working on in partnership with the National Organization for People Living with Hepatitis, and we are looking to see how we can support the patients in Uganda better. So, we are doing quite a number of things. We are doing advocacy at the community level, but also on a national level.

We have been able to push for inclusion of hepatitis services on the Global Fund and PEPFAR (President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief) fund in Uganda, and right now we are pushing for even more funding because previously they started funding the maternal child health testing for pregnant women, but we are now pushing for more than just testing for pregnant women. Also, with the new WHO guidelines on treatment, we are saying that we need to budget for treatment for these mothers. We need to do something, more support. We have also been part of campaigns that have pushed for national domestic funding for hepatitis, so we are doing quite a number.

My next question is if you could explain some of these partnerships in more detail…

So, I can give some more light on the partnerships. We are trying to see that our partnerships are diverse in terms of what we are doing with them. We are looking at partnerships with CSO’s (civil society organization) or organizations like ours, mainly to increase our impact on advocacy, but also service delivery. We are part of platforms that are supporting CSO’s that support HIV, making sure that hepatitis is integrated in all activities, all platforms of HIV, and all platforms of non-communicable diseases. We are pushing for integration.

We have made partnership with the Ministry of Health and we have an MOU with the Ministry of Health in Uganda which is giving us a better position to discuss and negotiate with the government better and support the planning for the hepatitis program, but also to be included in whatever action that takes place in the hepatitis programming in Uganda. Nationally, we have had partnerships with academia as I said, the religious leaders, the cultural leaders, but also the health workers. We are trying to build a network of health workers that are supporting hepatitis in Uganda, because the biggest challenge, one of the challenges we have here is capacity building and we have worked some to build the capacity of the health workers, to build the capacity of the journalists, and to build the capacity of village health workers, who are called the community health workers, but it is not enough.

So, some of these partnerships have been helping us in that way. Then globally, we are working with other African-based organizations to try and expand our impact as an organization, to learn from the achievements that we have made in Uganda, and to see how we can learn from them and make an impact in these other countries, because if we are to eliminate hepatitis before 2030, we should do it collectively because even if Uganda succeeds and these other countries around us are not succeeding in elimination, then we are doing nothing. For example, Egypt has been able to succeed when it comes to eliminating hepatitis C, but it is the only African country that has been approved or has been accredited as one that has kicked out hepatitis C completely, but that doesn’t count for us who are looking at Africa as a whole or kicking out hepatitis as a global health threat. It doesn’t work when you only have one country out of over 53 countries that is celebrating this, so we are now changing our approach from just looking at Uganda, because hepatitis is not limited by borders. It does not give respect to these borders, so we are trying to see, how do we use the lessons that we have learned, the experience that we have, the networks that we must support other organizations in in Africa or other governments in Africa, to reach the elimination goals. This is where we are now moving this year, pushing hepatitis aid organizations beyond borders and eliminating hepatitis in Africa. This is what we are pushing for.

You mentioned capacity building as one of the main challenges that you face, so my next question is: what are some other challenges that you face in addressing hepatitis, and other health concerns at the community level, how have you worked to overcome these, and are there any additional resources that would be helpful to have?

One of the challenges that we have is awareness. The community is not aware. We have political support, but to the extent [we need], no we don’t. The political support that we have is 3 million U.S. dollars. Yes, it is something based on other countries or other African countries, but when it comes to what we are fighting, it is nothing. It is like a mother who is trying to show that they are caring for their family, but they’re only giving one meal. It is really not enough. It is not sufficient to meet the elimination goals. So, we have a very big problem of resources, so we need to boost, or beef-up our resource mobilization for this.

We have a problem with the capacity in terms of knowledge for the health workers, but also the capacity in terms of the equipment and the technologies that are required to have a very good and strong sufficient response. You find that the technologies that we are using are outdated, we don’t have real time data, and nothing can be done without data, you know? It puts us to the back. We do not have all the data. Even the data we have from the WHO, it is just estimated data, we are using estimates. We need real data. When we talk about patients, we need to know how many patients there are. This will inform our planning. But we don’t have such data.

Also, we have a big problem with the supply chain for commodities for hepatitis. In Uganda, it has been over 6 months without commodities for hepatitis. It is over a year plus without treatment for hepatitis, and yet we are pushing for 0 transmission. Now, for example, if a mother with hepatitis B goes to a clinic and requires treatment to reduce the risk of transmission, how do we get her treatment in a country where treatment is not available? You know, we are in a country where we do not have a hepatitis C program and yet we are presenting with the hepatitis C patients. How are we going to go about this, you know? There is no commitment over hepatitis C and yet it is treatable.

So, these are some of the challenges that we have. We also have a problem of sustainability because, as an organization, our sustainability is based on individual gifts from people, people like us who decided to initiate these efforts. We are the ones that have to put in our monies and sometimes it gets extreme and sometimes you have to live a life, you have a family, you know.

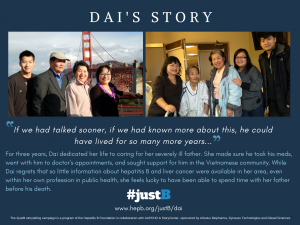

So, these are the challenges. As much as we are making progress, these are things that put us backward. Every step we make, we go backward. Also, one of the things that we believe is very important is awareness creation because when we communicate to the communities, it also communicates to the government, it communicates to everyone. It does not discriminate, and we do not have a behavior change campaign that is targeted to hepatitis. We have seen a lot of success in HIV elimination because of behavior change. So, one of the biggest challenges is that, without communication, without people knowing that there are these services, it creates underutilization, it creates wastage because the services are going to be expired, so these are things that we need to look at. Another challenge that I would look at is integration with other diseases and all that but to be honest, integration is not feasible because when you go to HIV for integration, they have their own interests. Their donors have their own interests. Donors like PEPFAR have their interests and they’re not directed by PEPFAR Uganda, they are directed by PEPFAR in the U.S. So, you find a country like Uganda which is having the anti-homosexual bill. Yes, it is about homosexuality, but you find that it is affecting all other health sectors. It is affecting all other donation avenues. So, these and more have really put us backward to a point that is almost [hard to] recover from.

So, when it comes to the barrier of awareness, what do you think are some of the biggest barriers against raising awareness and addressing rates of hepatitis screening and linkage to care at the local and national levels, and what more do you think can be done in this sphere of awareness building.

The biggest barriers to awareness are resources honestly because with resources, most of these barriers are no more. Then the capacity of the communities you know we have community health workers that we can rely on… they’re sustainable once they get the basics about these diseases. Once you train them on a disease, it is sustainable, but it also requires resources to build their capacity, and yet they are the firsthand persons that we talk to, that our people in the local communities go to for information even before they come to the hospital to the doctor. They know someone who is a community health worker, they first call them and say hey this and this, this person is presenting with this, you know, but the community health workers in Uganda know everything about HIV, everything about malaria, everything about measles, but nothing about hepatitis. … It could be better.

So, awareness starts with the community health workers?

Once we empower our communities, they will be the ones to ask for these services. Once we empower them, they will be the whistleblowers. Once we empower the communities, they will be the ones to talk to us and tell us A and B is not doing this. Even the stigma will automatically be fought once we empower the communities because now, they will be informed.

So, the last question, what are your favorite parts about your job and what got you interested in this work?

My favorite part of this job is basically networking and meeting new people. Whenever you get to these places, you meet new people and whenever you get calls from people that are inspired by your story, people that believe in what you say, people that keep pushing you to do more and get better, this is the best thing. Whenever you know that you’re doing something that is impacting your community positively. This is the biggest and greatest fulfillment that I have. As I told you earlier, I’ve been working with patients, cancer patients, and have been supporting cancer programs and supporting an HIV program before hepatitis, but I tested positive for hepatitis B in 2016 and when I tested positive, I didn’t know anything about it so this has been my biggest driver, how many people don’t know anything about hepatitis in my community. How many people are misled. How many people don’t have access to the services because they’re extremely expensive, so what can you do you know, and as a businessman when you see a problem, you find opportunity.

Thank you so much for speaking to me today. I really appreciated you sharing your experiences and perspectives.