Conference on Liver Disease in Africa

Conference on Liver Disease in Africa

To discuss the latest advances in addressing viral hepatitis and other liver diseases in Africa, there will be a virtual Conference on Liver Disease in Africa (COLDA) from September 10th to 12th, 2020. COLDA is organized by Virology Education on behalf of the organizing committee led by Drs. Manal Al-Sayed, Mark Nelson, and Papa Saliou Mbaye. This virtual conference will gather clinicians, patients, other healthcare professionals, and policymakers from African regions, with international experts to support and exchange innovative ideas and knowledge about liver disease. The conference will consist of lectures discussing viral hepatitis infections, hepatitis co-infections, non-viral hepatitis-related infections, non-infectious induced liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma, and end-stage liver disease. This virtual conference is important for addressing viral hepatitis since fewer than 1 in 10 people in Africa has access to testing and treatment for viral hepatitis. The World Health Organization (WHO) states that viral hepatitis is a bigger threat to Africa than HIV/AIDS, malaria, or tuberculosis with over 1.34 million deaths a year attributed to it.1 Over 60 million people in Africa have hepatitis B which annually accounts for an estimated 68,870 deaths.1 These statistics demonstrate the need for conferences like COLDA to discuss best practices and reduce viral hepatitis in Africa.

Mother-to-Child and Early Childhood Transmission

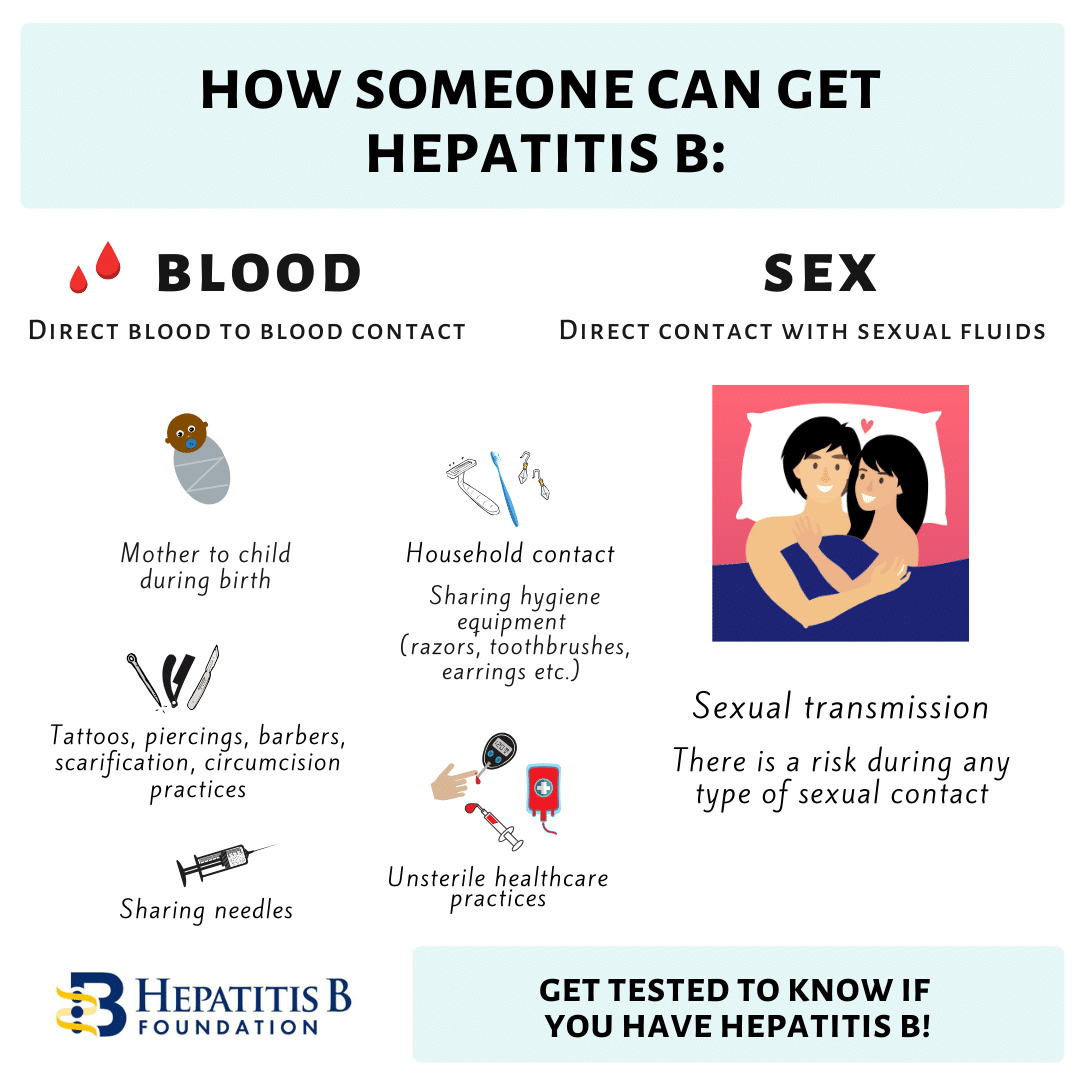

Hepatitis B is commonly transmitted from mother-to-child and close contact with infected individuals during the first 5 years of life. These modes of infection transmission are preventable with proper birth prophylaxis. There are two types of mother-to-child and early childhood transmission of hepatitis B resulting in chronic infection: vertical and horizontal. Vertical transmission refers to the transmission of hepatitis B from an infected mother to her baby during delivery. Horizontal transmission refers to infection with hepatitis B from direct blood-to-blood contact with an infected individual. Most early childhood transmission cases in sub-Saharan Africa are from horizontal transmission especially during the first 5 years of life from contact with family members or close friends infected with hepatitis B2, though vertical transmission from a hepatitis B infected mother to her baby is also common and completely preventable with birth prophylaxis.

The best way to prevent the transmission of hepatitis B (HBV) from mother to child is through a “birth-dose”, meaning infants are vaccinated against hepatitis B within 24 hours of birth. However, in the WHO Africa region, only 6% of infants are administered the birth-dose.1 Only three countries in Africa: Cameroon, Rwanda, and Mauritania, have national guidelines addressing mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B.2 Additionally, healthcare providers do not routinely screen future mothers for hepatitis B which contributes to a higher burden.2 This lack of screening demonstrates the need for universal guidelines to provide information to future mothers about hepatitis B. The World Health Organization recently released updated guidelines for hepatitis B which recommends a universal birth dose for all infants, as soon as possible, preferably within 24 hours followed by an additional 2-3 doses (often fulfilled with the pentavalent vaccine). Additionally, the WHO newly recommends that pregnant women testing positive for a hepatitis B infection (HBsAg positive) with an HBV DNA ≥ 5.3 log10 IU/mL (≥ 200,000 IU/mL) receive tenofovir from the 28th week of pregnancy until at least birth, to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HBV.4 This is in addition to the three-dose hepatitis B vaccination in all infants, including the timely birth dose. The WHO also strongly recommends that in settings in which antenatal (pre-birth) HBV DNA testing is not available, HBeAg testing can be used as an alternative to HBV DNA testing to determine eligibility for tenofovir prophylaxis to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HBV.4 Testing for hepatitis B in early pregnancy, a timely birth-dose, pentavalent vaccination, and administration of antivirals in the last trimester if needed would prevent vertical transmission and in turn, prevent horizontal transmission.

HIV/HBV Co-infection

There is a high burden of HIV/HBV co-infection in African countries because both diseases share similar transmission routes such as mother-to-child, unsafe medical and injection practices, and unscreened blood transfusions.2 Chronic HIV/HBV infection is reported in up to 36% of people who are HIV positive, with the highest prevalence reported in west Africa and southern Africa. The co-infection of HIV and HBV is especially dangerous because it accelerates liver disease such as fibrosis and cirrhosis. In fact, liver-related mortality is twice as high among people with an HIV/ HBV co-infection.2

Nosocomial Transmission

Another common way hepatitis B is transmitted in Africa is through nosocomial transmission or transmission from a hospital setting.3 The World Health Organization estimates 24% of blood donations in lower-income countries are not systematically screened for hepatitis B or hepatitis C. Additionally, countries have inconsistent screening procedures and use non-WHO prequalified test kits. Implementation of screening guidelines would significantly assist in reducing the risk of transmitting hepatitis B.

Barriers

There are numerous barriers to eliminating hepatitis B in African countries. Screening is costly and often inaccessible, especially in rural areas. Moreover, there is an irregular supply of test kits for screening for healthcare providers.2,3 Lack of public awareness and often provider knowledge also contributes to the higher hepatitis B burden. Research has found that less than 1% of Gambian adults previously knew their status when tested positive for HBsAg.3 Additionally, there are financial constraints when it comes to hepatitis B treatment and care. The World Hepatitis Alliance and the WHO found that 41% of the world’s population live in countries where there is no public funding for hepatitis B treatments.3 This financial barrier prevents people from accessing important screening and vaccination prevention services. A collaborative effort among governments, local health officials, and community members is needed to manage hepatitis B in African countries.

Importance of Conference

Hepatitis B disproportionately affects the WHO Africa Region where 6.1% of the adult population is infected.1 The Conference on Liver Disease in Africa will address problems and discuss potential solutions for this neglected preventable disease. COLDA will help to make eliminating hepatitis B in Africa a reality by engaging the global community to collaborate on public health efforts, develop innovative ideas, and discuss best practices to reduce barriers. We hope to see you there!

Learn more and register for the conference.

References:

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b

- Spearman, C. W., Afihene, M., Ally, R., Apica, B., Awuku, Y., Cunha, L., Dusheiko, G., Gogela, N., Kassianides, C., Kew, M., Lam, P., Lesi, O., Lohouès-Kouacou, M. J., Mbaye, P. S., Musabeyezu, E., Musau, B., Ojo, O., Rwegasha, J., Scholz, B., Shewaye, A. B., … Gastroenterology and Hepatology Association of sub-Saharan Africa (GHASSA) (2017). Hepatitis B in sub-Saharan Africa: strategies to achieve the 2030 elimination targets. The lancet. Gastroenterology & hepatology, 2(12), 900–909. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30295-9

- Maud Lemoine, Serge Eholié, Karine Lacombe, Reducing the neglected burden of viral hepatitis in Africa: Strategies for a global approach, Journal of Hepatology, Volume 62, Issue 2, 2015, Pages 469-476, ISSN 0168-8278, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2014.10.008

- Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus: guidelines on antiviral prophylaxis in pregnancy. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

On the other hand, hepatitis B begins as a short-term infection, but in some cases, it can progress into a chronic, or life-long, infection. Chronic hepatitis B is the world’s leading cause of liver cancer and can lead to serious liver diseases such as cirrhosis or liver cancer. Most adults who become infected with hepatitis B develop an acute infection and will make a full recovery in approximately six months. However, about 90% of infected newborns and up to 50% of young children will develop a life-long infection. This is because hepatitis B can be transmitted from an infected mother to her baby due to exposure to her blood. Many infected mothers do not know they are infected and therefore cannot work with their physicians to take the necessary

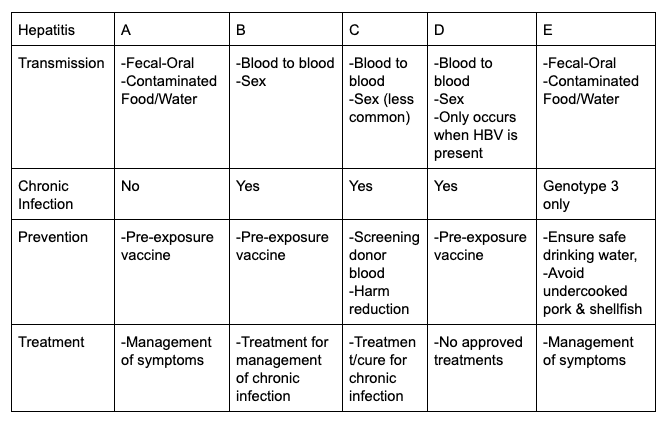

On the other hand, hepatitis B begins as a short-term infection, but in some cases, it can progress into a chronic, or life-long, infection. Chronic hepatitis B is the world’s leading cause of liver cancer and can lead to serious liver diseases such as cirrhosis or liver cancer. Most adults who become infected with hepatitis B develop an acute infection and will make a full recovery in approximately six months. However, about 90% of infected newborns and up to 50% of young children will develop a life-long infection. This is because hepatitis B can be transmitted from an infected mother to her baby due to exposure to her blood. Many infected mothers do not know they are infected and therefore cannot work with their physicians to take the necessary  With five different types of viral hepatitis, it can be difficult to understand the differences between them. Some forms of hepatitis get more attention than others, but it is still important to know how they are transmitted, what they do, and the steps that you can take to protect yourself and your liver!

With five different types of viral hepatitis, it can be difficult to understand the differences between them. Some forms of hepatitis get more attention than others, but it is still important to know how they are transmitted, what they do, and the steps that you can take to protect yourself and your liver!  that their primary mode of transmission is through direct blood-to-blood contact with an infected person. Also, both hepatitis B and C can cause chronic, lifelong infections that can lead to serious liver disease. Hepatitis B is most commonly spread from mother-to-child during birth while hepatitis C is more commonly spread through the use of unclean needles used to inject drugs.

that their primary mode of transmission is through direct blood-to-blood contact with an infected person. Also, both hepatitis B and C can cause chronic, lifelong infections that can lead to serious liver disease. Hepatitis B is most commonly spread from mother-to-child during birth while hepatitis C is more commonly spread through the use of unclean needles used to inject drugs.