Have you recently been told you have hepatitis B? Dealing with the diagnosis and waiting out the next six months to determine if your infection will resolve itself or learning that it is a chronic infection can be nerve-wracking.

Fortunately, greater than 90 percent of healthy adults who are newly infected will clear or resolve an acute hepatitis B infection. On the hand, greater than 90% of babies and up to 50% of children infected with hepatitis B will have lifelong, chronic infection. Sometimes people are surprised to learn they have a chronic infection. It can be confusing since there are typically few or no symptoms for decades. If a person continues to test hepatitis B positive for longer than 6 months, then it is considered a chronic infection. Repeat testing is the only way to know for sure.

Acute hepatitis B patients rarely require hospitalization, or even medication. If you are symptomatic, (some symptoms include jaundice, dark urine, abdominal pain, fever, general malaise) you may be anxiously conferring with your doctor, but if you are asymptomatic, you might not feel compelled to take the diagnosis seriously. Ignoring your diagnosis can be very serious. If you have concerning symptoms like jaundice (yellow eyes and skin), a bloated abdomen or severe nausea and vomiting, please see your doctor immediately. Your doctor will be monitoring your blood work over the next few months to see if you clear the virus, or monitoring your liver if there are concerning symptoms.

Your job is to start loving your liver …today. STOP drinking alcoholic beverages. Refrain from smoking cigarettes. Your liver is a non-complaining organ, but you cannot live without it. Make your diet liver-friendly and healthy filled with a rainbow of vegetables and fruits, whole grains, fish and lean meats. Minimize processed foods, saturated fats and sugar. Drink plenty of water.

Talk to your doctor before taking prescription medications, herbal remedies, supplements or over-the-counter drugs. Some can be dangerous to a liver that is battling hepatitis B. Get plenty of rest, and exercise if you are able.

Don’t forget that you are infectious during this time, and that loved ones, sexual partners and household contacts should be tested to see if they need to be vaccinated to protect against hepatitis B. Sometimes family members or close household contacts may find that they have a current infection or have recovered from a past HBV infection. If anyone fears exposure, ensure them that hepatitis B is not transmitted casually. They should get tested, and vaccinated if needed, and take simple precautions. Remind them that 1/3 of the world’s population will be infected with the hepatitis B virus during their lifetime.

On the flip-side… Do not let this new hepatitis B diagnosis consume you. As the weeks and months pass, you might find that the infection is not resolving, and you might worry that you have a chronic infection. The associated stress and anxiety can be challenging, even overwhelming. It can contribute to physical symptoms you may be experiencing. Find a family member, friend, or health care professional with whom you can share your concerns.

If you are told you have recovered from an acute HBV infection (you are now HBsAg negative, HBcAb positive and HBsAb positive) be sure to get copies of your lab reports to ensure there are no mistakes. Compare them with our easy to use blood tests chart. If something looks wrong, or if you’re confused, speak up and ask your doctor. Once confirmed, be sure to include hepatitis B as part of your personal health history. This is important in case you have conditions requiring treatment later in life that might once again warrant monitoring of your hepatitis B. It is possible for a past HBV infection to reactivate if a person requires longterm immune suppressing drugs .

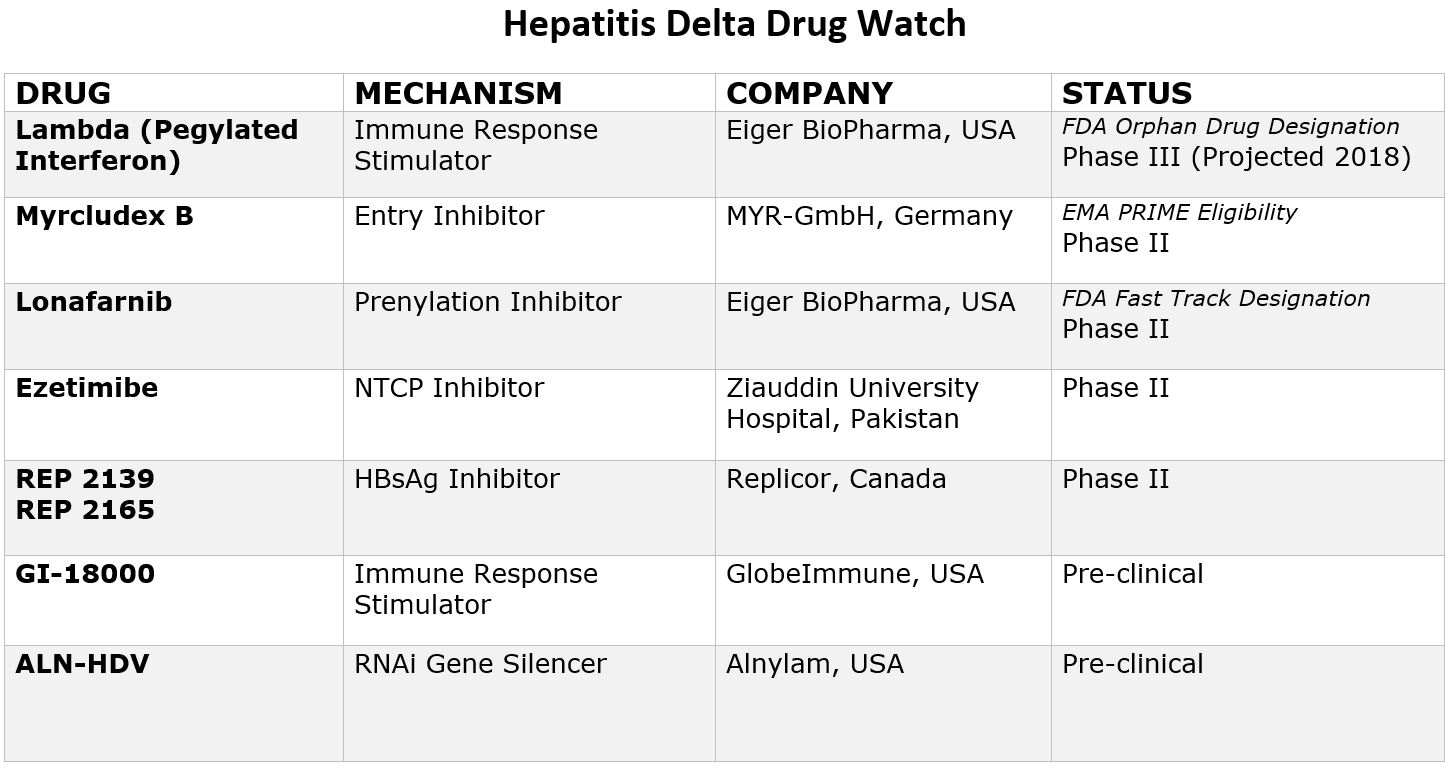

No one wants to learn they have chronic hepatitis B but it is a manageable disease. You’ll want to see a doctor with experience treating chronic HBV so they can run additional tests. There are very effective treatments available, though not everyone with chronic HBV needs treatment. All people living with chronic HBV benefit from regular monitoring since things can change with time. Please do not panic or ignore a chronic hepatitis B diagnosis. Take a deep breath and get started today learning more about your HBV infection and the health of your liver. Things are going to be okay!

If you are confused about your diagnosis, please feel free to contact the Hepatitis B Foundation at info@hepb.org.